The Linear Conundrum

Fifteen years ago I was in Milan at Salone del Mobile, considered the number one show for furniture and accessories in the world. Milan’s design week is the highlight of the design calendar, and the platform for leading brands to launch new ideas and products. It is an exciting place to visit, full of energy and innovation — a massive trade event on a colossal scale, with hundreds of aisles containing the latest furniture, lighting, kitchens and bathroom designs, as well as fabrics, wall coverings and cladding. Across the city in the edgier areas, you’ll find satellite shows from artisanal designer-makers, and as I see it, the more interesting and inventive pieces. You name it, Milan has it all. But as I walked through this maze of creativity and human endeavour, I began to wonder. Where had all these products come from? Not only that. Where do they go? And what happens to the products they are replacing?

Milan was one of a series of events that proved to be a catalyst for Kate and me to set up Sibley Grove. I had become increasingly conflicted about the design industry and could not find a positive message in the sea of consumerism and waste. I passionately believed in its power to do good, but it appeared to be broken, inherently throwaway and damaging to the environment. This damage is not purposeful or conscious but simply a result of the system we have, which has evolved over the last hundred years.

Looking around Milan, or any other trade show for that matter, I found it hard to feel enthusiastic about design. Rather than creating products or services of value that would enhance lives, the industry seemed distracted and preoccupied with tweaking existing products and marketing them as new and innovative to drive sales, exacerbating the problems linked to overconsumption, such as pollution, resource depletion and waste. Although the design industry significantly contributes to the economy, there seemed to be little value outside of that.

I found this stage of my design career very challenging because it was hard to justify creating something new (a view shared by many in the industry). Everywhere I looked, I saw gratuitous levels of waste. Rather than investing in research and development to make real progress, the design industry continued its obsession with adopting short-lived fashion cycles and building obsolescence into products to encourage further consumption. Fashion cycles are not a new thing; they have been a part of our culture since the birth of consumerism. But over time, they have engulfed the design industry, helping to build a frivolous culture of wastefulness — one where a product is rendered obsolete, not because of its utility but because of its style. The result is that we are using resources and discarding them on an unprecedented scale.

So who is to blame here? I certainly think that manufacturers, designers, brands and retailers are capable of doing a lot more from an environmental and ethical perspective. But it is difficult to have an impact because the problems are not individual but systemic. Many companies try to be better — environmentally and ethically — but often fail because they try to address the issues individually with a ‘what can I do?’ mentality. While this mindset is to be encouraged, it is far better to have a ‘what can we do?’ attitude. A collaborative approach that deals with all aspects of the supply chain, where businesses and individuals seek to influence and address the systemic problems linked to how we buy, use and dispose of goods. One that considers where materials come from and what happens to them after we have used them.

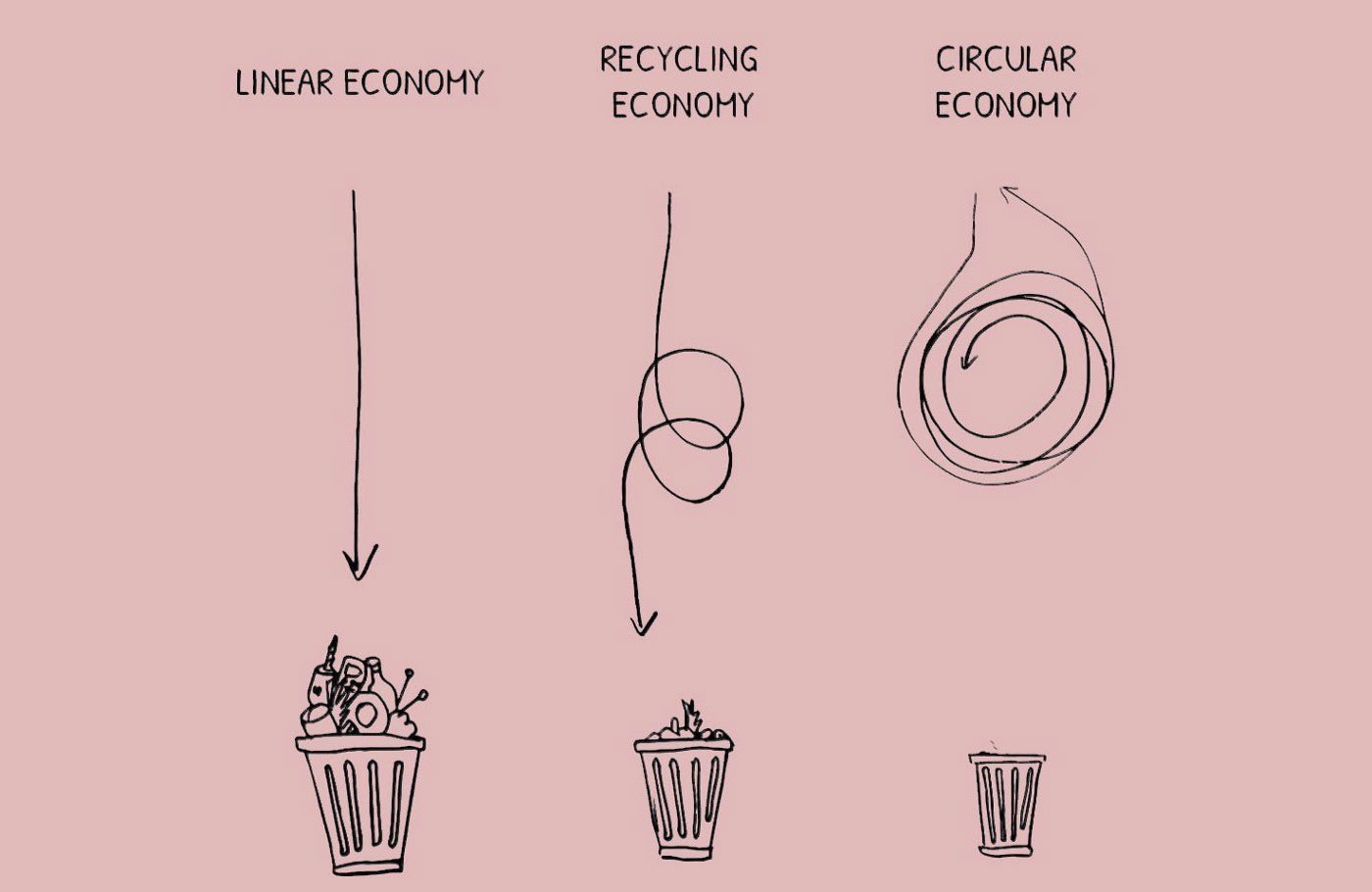

If we want to address the environmental and social inequalities within the design industry, then we start by acknowledging that our system of consumption is linear, a system that takes without putting anything back. In other words, we take raw materials and process them into products which end up as waste. Not because they are useless but because we have failed to design for this inevitable outcome. From the moment we start to manufacture the majority of our goods, we are consigning vast amounts of material to landfill or incinerators, be it five weeks, five months or five years down the line. Understanding and recognising this problem is the first step in addressing environmental and social inequality.

There are many examples of companies trying to produce so-called sustainable products, but they are based on a linear system. As long as the system of delivery promotes waste, then the best anyone can ever do is to limit the negative impact, and this should be the very lowest of our goals, and certainly nothing to shout about. If designers, manufacturers and retailers remain wedded to this system, then little will change. We must unpick the linear model which underpins the global economy, and create a strategy based on quality and lasting value rather than waste.

To better understand the process and its impact, I have broken the linear system into four main categories, which I will explain further; 1) materials and resources, 2) manufacturing, 3) retail, marketing and consumption, 4) waste.

Materials and resources

The linear system begins with resources, which are extracted from the earth and processed into usable materials. These can be renewables such as timber and natural fibres or non-renewables such as ore and oil attained through mining or drilling, which are converted into metals, plastics etc. As we move into the future, the world’s resources will become increasingly precious, and a linear system with accelerated consumption levels only intensifies the pressure on our resource base. The unrelenting demand can lead to prolonged environmental damage and resource scarcity because it is a system that takes without putting back or allowing nature to regenerate. As global demand for materials increases, the negative impact of the linear system is becoming increasingly apparent. In the case of renewables like timber, the appetite for material can outstrip the growth of new trees, leading to deforestation. But it can also destabilise and destroy delicately balanced ecosystems evolved over millions of years — systems of plants and animals that underpin and sustain the natural world.

In terms of non-renewables, the linear system poses another set of significant challenges. Firstly, extraction carries a high degree of risk because it will always damage the surrounding environment and permanently alter the landscape. In extreme cases, the stark reality of those risks becomes all too clear, such as the BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion, which released 130 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010. The impact of that incident on fish, turtles, birds and marine mammals is still felt today and will continue for many years to come. The truth is that businesses can only manage or limit the impact of extraction. It is a process where the environment and economy are in direct conflict, and in most cases, the economic factors prevail. In resource-rich countries with weak governance, it can lead to the accumulation of long-term ecological damage for short-term capital gains. It’s not to say that these materials should stay in the ground or that extraction is fundamentally wrong — quite the opposite. These materials are essential to our way of life — a key component in every facet of our lives. However, non-renewable materials are finite resources that can’t be replenished, and in a consumer culture, based on a linear system, we use up metals, oils, and rare earth minerals in cheap throwaway consumer goods. All the costs, risks, and environmental damage associated with extraction are for nothing. It is not a sensible long-term strategy.

Manufacturing

The second stage of a linear system is manufacturing, in other words, converting raw materials into usable materials and products. There are two critical challenges in play here.

First of all, we must remember that in this system, once a product gets to the end of its lifecycle — otherwise known as the ‘product lifecycle’ — it is typically discarded as waste. The material has little value to anyone. As a result, the manufacturers have no incentives to think about recyclability or future functionality, so materials are processed with a temporary, short-term mindset. To effectively reuse material, products must be designed for disassembly; however, because this is rarely a consideration at the design stage, the vast majority of the material is wasted in landfill or incinerated because it is too costly to retain.

Second, for our consumer-driven model to work, we must maintain — better grow — consumer demand. One effective strategy is to keep goods cheap enough so people can afford to throw them away. In doing so, downward pressures are applied across the manufacturing sector to reduce costs, leading to the exploitation of materials and labour higher up the supply chain. The demand for cheaper products forces manufacturers to outsource production to parts of the world with weaker environmental regulations and reduced labour rights. But it also applies pressure on the procurement of materials and resources, exacerbating issues like deforestation and illegal logging or exploitation in the mining sector.

Retail, marketing & consumption

The next point in the process is retail and marketing, which drives sales and boosts consumption levels. Unfortunately, in a linear system, modern retail and marketing techniques are like pouring petrol on a fire that is getting out of hand. Humans have traded goods and services for hundreds of years, but materials and products are being exchanged and consumed faster than at any point in human history. Modern retail and marketing are at the centre of this crisis, ratcheting up demand whilst remaining disconnected, and in some cases indifferent, to the worsening issues. You might get the odd emotive advert proclaiming how much a brand loves the oceans or how its plastic bottle design uses 50% recycled plastic (even though they always have). Unfortunately, the vast majority of businesses favour brand messaging over practical solutions and remain firmly tied to a linear system and the problems that go with it. While that remains the case, increased consumption will only place greater demand on resources.

But is modern retail such a problem? It seems harmless enough. After all, retailers rarely make the stuff, and they don’t tell us to throw it away. Well, that’s not necessarily true. While strategic marketing campaigns help inform the public about the latest products and services, they also encourage the disposal of existing items. By conjuring up needs and desires, our appetites remain. Historically, built-in obsolescence was about a technical and terminal product failure requiring the customer to make a new purchase — a practice still commonly seen in the tech industry with the annual replacement of smartphones. But there are many more sophisticated ways to encourage people to replace old things with new ones. Fashion cycles or style changes have proven effective ways to promote and encourage the replacement of goods when the previous model remains unimpaired in its utility. Trends in colour can boost sales of small items like clothing, home accessories and kitchen utensils, while style changes can lead to greater investments such as cars, bathrooms suites, kitchens and furniture.

The trends and fashion cycles utilised by the retail and marketing sectors help develop a culture of short-term fulfilment, keeping the masses dissatisfied. In a linear system of consumption, society needs to remain unfulfilled and hungry for more. Businesses must continually create wants and desires that exceed our basic needs, encouraging us to pine for things in a constant quest for happiness and contentment. It is a fruitless pursuit and a never-ending journey. By bombarding us with ad campaigns that point out our failures and shortcomings while simultaneously pitching us solutions, we continue to buy and consume. The beauty of this system of consumption is that businesses are continually reinventing products. No sooner have you made one purchase, another product will emerge the following year, ‘new and improved’. This continual evolution ensures society remains hungry, gripped for the next fix.

Waste

So, where does this leave us?? The desire to consume inevitably leads to waste, the final stage in the linear system. Waste is a human creation which doesn’t form part of nature’s language. In all aspects of nature, discarded material serves a purpose, whether that’s building materials for animals, food for organisms or nourishment for plant life. The changing state of a material is an essential part of nature’s cycles, played out through the seasons. Humans created the concept of waste, materials that pollute, can’t be reintegrated with the natural world and have no utility. They’ve become a burden. This unwanted material ends up in landfills and incinerators because it is unusable and economically unviable.

It is easy to imagine the physical waste we discard in our own lives at the rubbish tips or in our dust bins, even though few of us comprehend the sheer scale of waste when multiplied across the global population. But we often forget to quantify the trail of destruction along all key stages of the linear system. The environmental damage during extraction, both short term and long term. The consumption of vast amounts of energy. The accumulative pollution through irresponsible manufacturing or the over-reliance on exploited labour markets. The linear system delivers economic results, and it’s foolish to ignore the benefits that consumerism has brought us in terms of social development. But while we benefit from short-term economic growth, we build up long-term environmental damage, which will become an economic and social burden both now and in the future.

Summary

By the time Kate and I set up Sibley Grove, we had come to realise that the linear system was at the centre of a lot of the environmental and social problems created by the design industry. But identifying a problem is the easy part. The difficulty lies in finding a solution because the problem is complex. Over the last one hundred years, the approach to how we buy and consume goods has become so ingrained into our culture and our DNA that we barely see the structural problems. It isn’t something any of us have ever had to question; it’s just the way it is. The uncomfortable truth for many people — in particular, environmentalists — is that this system has been one of the most influential and beneficial in human history. The vast majority have benefited from continued economic growth, and we have grown to depend on this system to bring relative stability and get us out of financial hardship. Yes, big businesses make vast amounts of money and have worryingly grown so large that they consolidate wealth and power. But many people have benefited from a continual supply of cheaper affordable goods. If it weren’t a mutually beneficial system, then it would have collapsed a long time ago. However, although this system works on the face of it, it doesn’t hide the fact that it is defective and we urgently need something better.

Personally, I found the first year at Sibley Grove especially difficult because I had underestimated the scale of the problem. I had assumed that we could be a more ‘sustainable’ design company by using better materials — preferably recycled — increasing our efficiency and reducing waste. But while these are all helpful measures, they only scratch at the very surface of the problem. In a linear system, we create huge volumes of waste that can’t be reused or discarded safely. The vast majority of this waste goes to landfill or is incinerated. If we stick with this system, it raises the question: What level of waste is okay? There is no reasonable scenario where we consume finite resources in ill-conceived consumer goods before shoving them, irredeemably, into a big hole. Whether they are produced by huge manufacturers overseas or local artisans, it’s still waste. So, where do we draw the line? I realised that it was impossible to create positive outcomes based on a linear system. All we can do is reduce our impact.

Over the last one hundred years, our capacity to produce and consume has grown unabated, but the system that holds it together has barely evolved. The linear system is fundamentally flawed, and any intervention from an environmental perspective is going to be negative. One school of thought is that to be more ‘sustainable’ we need to consume less and be more efficient. While that is always broadly speaking necessary, it is a wholly unambitious target and also fails to take into account the economic fallout. The systemic problems are those that are most urgent and in need of attention. Simply slowing down the linear system will have some environmental benefits in the short term. Still, it is not an effective long-term strategy, nor is it appropriate because the economic damage would be enormous. We need to reduce the amount of material that becomes waste, which in turn reduces the demand on resources. Not by consuming less but by designing in such a way that materials maintain their utility in perpetuity.

I have always thought that design is about creating positive outcomes that benefit people and the environment, but in my work, it seemed increasingly impossible to make a positive contribution. Less than a year into trading, the business felt rudderless. We were very busy with work, but the truth is that I was losing faith in our business plan. We were pitching ourselves as ‘sustainable’, but deep down, it did not feel like our work had a genuine impact. It felt like we were two businesses; the one we wanted to be and the one we were. If we wanted to succeed in our mission to break the cycle of waste and exploitation, then we needed to find a better way of working and a credible solution.

Most of us understand the importance of a strong economy, social progress, and a healthy, flourishing environment. But while design and manufacturing remain wedded to a linear system of consumption, profit, nature and social equality will always be conflicting factors. The solution lies in reconciling these three elements and finding an approach that is mutually beneficial. Environmental choices that make economic sense and profitable outcomes that benefit the environment.

As a design practice, we began to interrogate our work and ask honest questions. If we found something we did not like, then we had to dig deeper rather than turn the other cheek. We had to have a greater understanding of our industry's impact on the environment, people and the economy and invest time in understanding the supply chain, researching solutions, and building a network of collaborators.

The best designs are process-driven, but designers tend to gravitate towards predetermined outcomes. However, we must follow the research to create the appropriate solutions. When confronted with the environmental and social problems of today, it is easy to focus on outcomes such as deforestation, greenhouse gases, and ocean plastic. But outcomes are not the problem, they are consequences of the problem. If a bathtub is overflowing with water, you don’t pick up a bucket to start bailing out the water, you switch off the tap. To create solutions, we need to address the system of delivery. To tackle the inputs and human behaviours at the centre of the problem, such as the linear system.